When Alan DeKok began a side project in network security, he didn’t expect to start a 27-year career. In fact, he didn’t initially set out to work in computing at all.

DeKok studied nuclear physics before making the switch to a part of network computing that is foundational but—like nuclear physics—largely invisible to those not directly involved in the field. Eventually, a project he started as a hobby became a full-time job: maintaining one of the primary systems that helps keep the internet secure.

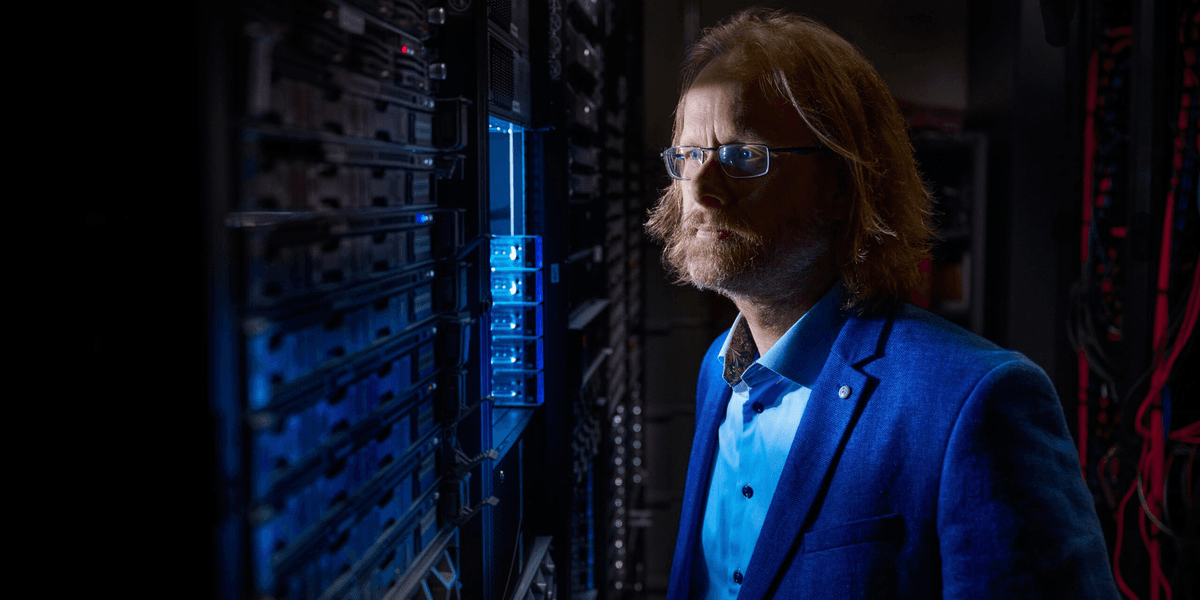

Alan DeKok

Employer

InkBridge Networks

Occupation

CEO

Education

Bachelor’s degree in physics, Carleton University; master’s degree in physics, Carleton University

Today, he leads the FreeRADIUS Project, which he cofounded in the late 1990s to develop what is now the most widely used Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service (RADIUS) software. FreeRADIUS is an open-source server that provides back-end authentication for most major internet service providers. It’s used by global financial institutions, Wi-Fi services like Eduroam, and Fortune 50 companies. DeKok is also CEO of InkBridge Networks, which maintains the server and provides support for the companies that use it.

Reflecting on nearly three decades of experience leading FreeRADIUS, DeKok says he became an expert in remote authentication “almost by accident,” and the key to his career has largely been luck. “I really believe that it’s preparing yourself for luck, being open to it, and having the skills to capitalize on it.”

From Farming to Physics

DeKok grew up on a farm outside of Ottawa growing strawberries and raspberries. “Sitting on a tractor in the heat is not particularly interesting,” says DeKok, who was more interested in working with 8-bit computers than crops. As a student at Carleton University, in Ottawa, he found his way to physics because he was interested in math but preferred the practicality of science.

While pursuing a master’s degree in physics, also at Carleton, he worked on a water-purification system for the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, an underground observatory then being built at the bottom of a nickel mine. He would wake up at 4:30 in the morning to drive up to the site, descend 2 kilometers, then enter one of the world’s deepest clean-room facilities to work on the project. The system managed to achieve one atom of impurity per cubic meter of water, “which is pretty insane,” DeKok says.

But after his master’s degree, DeKok decided to take a different route. Although he found nuclear physics interesting, he says he didn’t see it as his life’s work. Meanwhile, the Ph.D. students he knew were “fanatical about physics.” He had kept up his computing skills through his education, which involved plenty of programming, and decided to look for jobs at computing companies. “I was out of physics. That was it.”

Still, physics taught him valuable lessons. For one, “You have to understand the big picture,” DeKok says. “The ability to tell the big-picture story in standards, for example, is extremely important.” This skill helps DeKok explain to standards bodies how a protocol acts as one link in the entire chain of events that needs to occur when a user wants to access the internet.

He also learned that “methods are more important than knowledge.” It’s easy to look up information, but physics taught DeKok how to break down a problem into manageable pieces to come up with a solution. “When I was eventually working in the industry, the techniques that came naturally to me, coming out of physics, didn’t seem to be taught as well to the people I knew in engineering,” he says. “I could catch up very quickly.”

Founding FreeRADIUS

In 1996, DeKok was hired as a software developer at a company called Gandalf, which made equipment for ISDN, a precursor to broadband that enabled digital transmission of data over telephone lines. Gandalf went under about a year later, and he joined CryptoCard, a company providing hardware devices for two-factor authentication.

While at CryptoCard, DeKok began spending more time working with a RADIUS server. When users want to connect to a network, RADIUS acts as a gatekeeper and verifies their identity and password, determines what they can access, and tracks sessions. DeKok moved on to a new company in 1999, but he didn’t want to lose the networking skills he had developed. No other open-source RADIUS servers were being actively developed at the time, and he saw a gap in the market.

The same year, he started FreeRADIUS in his free time and it “gradually took over my life,” DeKok says. He continued to work on the open-source software as a hobby for several years while bouncing around companies in California and France. “Almost by accident, I became one of the more senior people in the space. Then I doubled down on that and started the business.” He founded NetworkRADIUS (now called InkBridge Networks) in 2008.

By that point, FreeRADIUS was already being used by 100 million people daily. The company now employs experts in Canada, France, and the United Kingdom who work together to support FreeRADIUS. “I’d say at least half of the people in the world get on the internet by being authenticated through my software,” DeKok estimates. He attributes that growth largely to the software being open source. Initially a way to enter the market with little funding, going open source has allowed FreeRADIUS to compete with bigger companies as an industry-leading product.

Although the software is critical for maintaining secure networks, most people aren’t aware of it because it works behind the scenes. DeKok is often met with surprise that it’s still in use. He compares RADIUS to a building foundation: “You need it, but you never think about it until there’s a crack in it.”

27 Years of Fixes

Over the years, DeKok has maintained FreeRADIUS by continually making small fixes. Like using a ratcheting tool to make a change inch by inch, “you shouldn’t underestimate that ratchet effect of tiny little fixes that add up over time,” he says.

He’s seen the project through minor patches and more significant fixes, like when researchers exposed a widespread vulnerability DeKok had been trying to fix since 1998. He also watched a would-be successor to the network protocol, Diameter, rise and fall in popularity in the 2000s and 2010s. (Diameter gained traction in mobile applications but has gradually been phased out in the shift to 5G.) Though Diameter offers improvements, RADIUS is far simpler and already widely implemented, giving it an edge, DeKok explains.

And he remains confident about its future. “People ask me, ‘What’s next for RADIUS?’ I don’t see it dying.” Estimating that billions of dollars of equipment run RADIUS, he says, “It’s never going to go away.”

About his own career, DeKok says he plans to keep working on FreeRADIUS, exploring new markets and products. “I never expected to have a company and a lot of people working for me, my name on all kinds of standards, and customers all over the world. But it worked out that way.”

This article appears in the March 2026 print issue as “Alan DeKok.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web